It’s disconcerting to find so few faces in the prominent ranks of the environmental movement that reflect the realities and experiences of those bearing the brunt of climate collapse. Estimates show that since 1990 more than 90% of natural disasters have occurred in poor countries and that, globally, communities of color have been disproportionately impacted by air, soil and water pollution. Numbers also demonstrate that low-income households are hit the hardest by disasters, due to factors such as poor infrastructure and economic instability.

Yet those making strategic decisions are sitting in air-conditioned board rooms, hoping their conversations will pave the way for profound systemic change. Those most impacted by socioeconomic ills and environmental degradation are rarely present at those tables. This disconnect is quite alarming. Those of us frustrated with this scenario have turned to a deeper analysis and framework over the last decade—that of climate justice. Defining climate justice is a work in progress; honoring and integrating it are lifelong struggles.

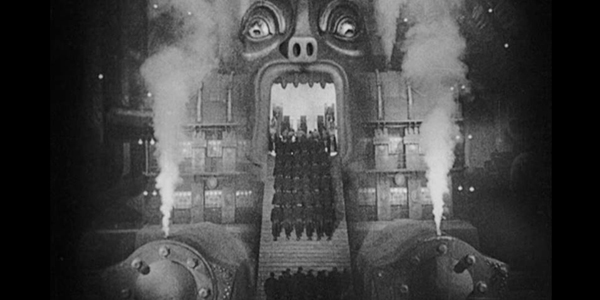

To tackle the root (read: radical) causes of the climate crisis, we must first acknowledge that environmental degradation exacerbates existing economic, racial and social injustices—an interconnectedness that should define our analysis and actions. To truly win, land and justice defenders must recognize overlapping systems of oppression within this capitalist structure, and take strategic cues from the communities most impacted by colonization, militarism and poverty. That means building movements across issues and beyond divides based on race, class and gender, while elevating the voices that have been historically marginalized: indigenous peoples, communities of color, women, LGBTQ people, and the low-income population. To do so will take a profound decolonization of minds and professional institutions.

For many in this country, resistance isn’t a choice—it’s not fashionable—it’s plain survival.

Walking through the streets of northern Philadelphia, my heart sinks. The rundown streets of a forgotten city, its gifts and peoples deemed disposable by the state’s corporate and governmental elites. Empty lots, dozens of schools shut down, despairingly long waiting-lists for access to public education, while across the invisible divide, bright lights shine and champagne glasses clink, unperturbed.

In the Far Rockaways of New York City, I come across wounds still bleeding, left open to the winds. Memories of Hurricane Sandy lie in the debris lining the sidewalks, the closed-down businesses and uneven pavements, the local hospital on the brink of closure. The mass incarcerations of our brothers, fathers, lovers of color, stuck in vicious cycles of debt, drugs and street violence, the straight shot from a poor home to a gray prison cell. The overflowing detention centers, filled with terrified youth ripped from their families, many of them waiting to be deported to countries they haven’t set foot in since early childhood. Indigenous nations, whose land we’re standing on, surviving 500 years of cultural and ethnic genocide, in the form of boarding schools, involuntary sterilization of their women, and broken treaties.

These are the unsung faces of the resistance. The warriors whose lived experiences and very survival should not only drive the direction of our movements, but will inevitably determine the success of our struggle for collective liberation.

Instead, within the existing mainstream culture, while organizing has shifted to career-based models, anti-oppression work has become fashionable, and even worse, fundable. Through trainings, some may have learned the politically correct language to use, but much of the “anti-oppression” process has remained superficial, void of a real consideration for intersections of race, class and gender. This has resulted in a few token organizers of color hired into the ranks of respectable positions in big non-governmental organizations, with an unspoken expectation that they will be speaking for other brothers and sisters of color. Meanwhile, for those coming from low-income households or without a college education, the doors of opportunity within the environmental and climate movement are almost always out of reach.

For a person once seduced by an organizing career and its false promises of liberation, it was a rude awakening. As a brown migrant woman, often tokenized as the “good kind of Arab,” if I wanted a meaningful voice in this movement, I was going to have to take up space for myself, much like many had done before me. That also meant taking responsibility for my own layers of privilege, like my college education and access to resources, that most in my family aren’t privy to.

The professionalization of change-making has created a non-profit industrial complex (NPIC) which hinders rather than promotes liberationist movements. At Power Shift 2011, a national climate conference bringing together thousands of youth, there was a literal physical divide between the workshop spaces for the college students (mostly white middle-class) and the front-line communities (low-income, mostly youth of color). Since they were assigned different training tracks and curriculum, one of the only overlaps was during keynote speeches.

This year, at the same conference, several delegations of marginalized youth (Lakota youth from the Pine Ridge reservation, Dream Defenders from Florida, and impacted Gulf Coast communities from TEJAS) were promised funds for food and transportation that were either never or only partially delivered. These practices are counter-productive to social change, as they perpetuate the very systemic oppression we’re fighting.

Meanwhile, NGOs are competing for membership and campaign victories, racing for measurable results that will prove to their funders that they deserve yet more money. In a nine-year period, big greens received over $10 billion in funding, with only 15% of grants (between 2007-2009) allotted to marginalized communities. This discrepancy is appalling, especially given the fact that more money means more institutional costs and infrastructure, which often translates to compromises and watered-down actions. This top-down funding strategy ignores the history of resistance—that large-scale social change stems from the grassroots and a sturdy leadership from the oppressed peoples who have a vested interest in fighting for freedom.

It’s hard to imagine a popular uprising being initiated by those relying on the comforts of paychecks and organizational stability, so those voices shouldn’t dominate the narrative. Often it’s professional activists heard shouting into megaphones, calling for escalation and taking it to the streets. As economies crash, natural disasters multiply, and countries are torn apart by war, that call rings true.

But what happens when an organization like MoveOn.org adopts Occupy’s grassroots message for the purpose of publicizing nationwide direct action trainings, but discourages trainers from promoting civil disobedience because of their organizational politics? Or when the Natural Resources Defense Council and World Wildlife Fund work with the fossil-fuel industry, the latter quite satisfied to buy them out and define their own opposition in the process? Or when 350.org calls for escalation in the resistance to the Keystone XL pipeline, fundraise from other individuals’ bold actions in one of their email asks, but when those front-line activists face potential felony charges, leave them unsupported due to lack of organizational foresight and adequate infrastructure? These examples show a disconnect and an inability to build genuine relationships with those on the ground.

With budgets and voices so loud, the professionals’ messages overshadow the call for uprisings coming from the trenches. Though those cries may not be amplified by megaphones or on the front pages of websites, they can be heard rumbling through the neighborhoods, detention centers, prisons, native reservations, homeless shelters, and broken-down apartment buildings.

So the question is, how will the mainstream respond when front-line communities take to the streets, when communities of color reclaim our power and stand our ground? Will the movement be ready and willing to demonstrate intentional and genuine solidarity?

With anti-oppression on the tip of everyone’s tongues these days, it is critical to remind ourselves that working with those who’ve been historically oppressed is not about atonement of guilt, stroking of egos, or moving personal agendas forward.

Andrea Smith refers to this in a recent piece, as an “entire ally industrial complex (that) has developed around the professional confession of privilege.” This practice of atonement perpetuates power imbalances by re-centralizing the voices and experiences of those carrying historical privilege, this time elevating them to the role of righteous confessors. This “anti-oppression” work Smith writes about is missing the mark entirely.

From Naomi Klein to Van Jones, from organizers of the ’99 WTO protest to blockaders of the Keystone XL pipeline in Texas, a similar message resonates: the non-profit industrial complex needs to deepen its class analysis, tackle white supremacy within its own institutions, and dump the colonialist “savior” syndrome. Professional activists must challenge institutionalized and structural privilege within their own organizations, in terms of air time, resources, influence, and how much space they take up.

What can professional activists do to decolonize the mainstream movement? Make financial resources available to those communities that need it most, rather than filling the bank accounts of multi-million-dollar organizations. Open up seats at the decision-making table for the freedom fighters on the front lines, rather than inviting them for the photo op once all the strategy has been laid out. Get out of the way when those whose stories must be told are speaking up, rather than writing up studies about their experience. Take the time to learn and practice genuine allyship that doesn’t translate to condescending tokenism.

To reflect integrity, this process cannot be driven by the need for personal and organizational recognition. Challenging our own internalized -isms is a constant work in progress, one that can take a lifetime. From the jungles of Mexico, the Zapatistas wisely remind us of the longevity of this process, that we must walk on asking questions—”preguntando caminamos.”

To those of you on the front lines, to the brothers and sisters of color wearing ancestors in our flesh, carrying in our bodies the historical traumas of a system designed to break our spirits and exterminate us, it is a testament to our resilience that we’re still here, that we’ve survived over time. To those who still wonder when the time for a radical shift will come, it has. Our day-to-day reality won’t be getting scary somewhere down the road, in some distant future—there’s a war being waged against our communities right now!

In this day of climate crises and economic collapse, of lingering white supremacy and patriarchy, the struggle is as much about resistance as it is about community survival programs, as much about taking down the fossil fuel industry as decolonizing our own minds. This moment calls upon us to get real about what that will take from us, what the responsibilities entail, and what real solidarity looks like.

If this movement is serious about winning and shifting our current paradigm, we are going to have to give up some comforts and get out of the way when the times call for it.

Hénia Belalia is on the National Coordinating Committee of Deep Roots United Front, and the former director of Peaceful Uprising. She identifies as a climate justice defender, theatre director and day dreamer of collective liberation. Her work is rooted in a constantly evolving practice of allyship to frontlines of struggle, with a focus on the intersections of environmental and social justice.

– – – – – – – – – –

Originally posted by AlterNet.