I cried today. Not once, not twice. Maybe I cried eight times. I’m not even sure how to separate one cry from the next, when my heart carries sadness and anger in waves from peak to ebb, ebb to peak.

The exact number doesn’t matter.

I’m not used to crying. As a male, socialized into masculinity, I learned to suppress grief and most other strong emotions at an early age. I remember the last time I cried in front of my mother, at perhaps 12 or 13 years old. I don’t remember why I cried, but I do remember (and this is why I remember) my guilt and shame around breaking down in such a way, mixed into my sadness and into the comfort I received from her. I haven’t cried much since then.

I can give an easy proximate cause for today’s release: two heart-wrenching movies. But I need to explore some background for it to really make sense.

Portland

I lived nine years in Portland, where, after an initial period of frustrating and ineffective involvement in national and local politics, my then-partner and I embarked on a path of “disconnecting from civilization.” We aimed to develop the practical skills necessary to eventually move to land, create a “tribe” of close-knit community members, and establish self-sufficient subsistence via homesteading and hunting & gathering. I learned how to integrate some of my “waste” products of humanure, greywater, and kitchen scraps into my food system. I learned enough basic construction to build simple shelters. I planted food forests and a perennial vegetable garden to learn how to feed myself efficiently while creating wildlife habitat and sequestering carbon. I learned about those other cohabitants of our landbase, and even learned to listen to them in my attempts to understand the non-civilized world. I played with “rewilding” crafts skills. I talked with three successive groups of potential tribe-mates, and learned some of the difficulties of communication, of connection, of finding shared purpose, of resolving conflict.

At the same time, I engaged with the larger community, trying to share what I was learning and inspire others to disconnect, in part or whole, from the destructive systems of industrial civilization. I offered free tours and presentations and classes, blogged more or less frequently to document my experiments and findings, and provided edible and useful plants and seeds at low cost. I was something of a “food activist”, specializing in advocacy of perennial polycultures.

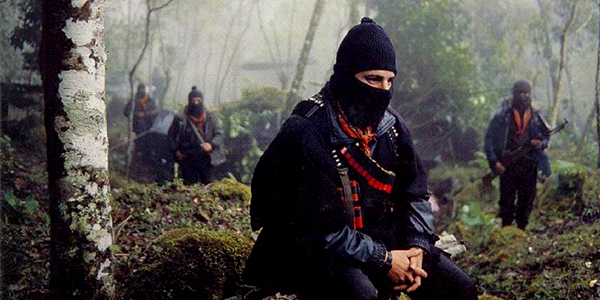

And at the same time, I knew it wasn’t enough: neither my own personal withdrawal, nor sharing my skills and encouraging others to move towards true sustainability. I couldn’t escape the reality and the challenge presented most eloquently by Derrick Jensen: the culture of civilization is insane and intent on destroying everything on this planet, and it will not voluntarily stop. Withdrawal and teaching are both legitimate responses to the threats of social, economic, and environmental instability, but are inadequate without forming a serious resistance movement to halt civilization.

Although I knew at some point I would need to take part in some form of resistance, I tucked that goal away. I rationalized that I needed to focus on getting myself and a tribe into a stable position on land of our own before I could put energy into addressing the big picture, long-term struggle.