Architecturally, a keystone is the wedge-shaped piece at the crown of an arch that locks the other pieces in place. Without the keystone, the building blocks of an archway will tumble and fall, with no support system for the weight of the arch. Much of the United States climate movement right now is structured like an archway, with all of its blocks resting on a keystone — President Obama’s decision on the Keystone XL pipeline.

This is a dangerous place to be. Once Barack Obama makes his decision on the pipeline, be it approval or rejection, the keystone will disappear. Without this piece, we could see the weight of the arch tumble down, potentially losing throngs of newly inspired climate activists. As members of Rising Tide North America, a continental network of grassroots groups taking direct action and finding community-based solutions to the root causes of the climate crisis, we believe that to build the climate justice movement we need, we can have no keystone — no singular solution, campaign, project, or decision maker.

The Keystone XL fight was constructed around picking one proposed project to focus on with a clear elected decider, who had campaigned on addressing climate change. The strategy of DC-focused green groups has been to pressure President Obama to say “no” to Keystone by raising as many controversies as possible about the pipeline and by bringing increased scrutiny to Keystone XL through arrestable demonstrations. Similarly, in Canada, the fight over Enbridge’s Northern Gateway tar sands pipeline has unfolded in much the same way, with green groups appealing to politicians to reject Northern Gateway.

However, the mainstream Keystone XL and Northern Gateway campaigns operate on a flawed assumption that the climate movement can compel our elected leaders to respond to the climate crisis with nothing more than an effective communications strategy. Mainstream political parties in both the US and Canada are tied to and dependent on the fossil fuel industry and corporate capitalism. As seen in similar campaigns in 2009 to pass a climate bill in the United States and to ratify an international climate treaty in Copenhagen, the system is rigged against us. Putting Obama and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper at the keystone of the archway creates a flawed narrative that if we, as grassroots groups, work hard enough to stack the building blocks correctly to support them, then elected officials will do what we want. Social change happens when local communities lead, and only then will politicians follow. While we must name and acknowledge power holders like Obama, our movement must empower local communities to make decisions and take action on the causes of the climate crisis in their backyards.

Because of the assumption that the climate movement can trust even “sympathetic” politicians like Obama, these campaigns rely on lifting up one project above all else. Certain language used has made it seem like Keystone XL is an extreme project, with unusual fraud and other injustices associated with it. Indeed the Keystone XL project is extreme and unjust, as is everyfossil fuel project and every piece of the extraction economy. While, for example, the conflict of interests between the State Department, TransCanada and Environmental Resources Management in the United States, and Enbridge and federal politicians in Canada, must be publicized, it should be clear that this government/industry relationship is the norm, not the exception.

The “game over for climate” narrative is also problematic. With both the Keystone and Northern Gateway campaigns, it automatically sets up a hierarchy of projects and extractive types that will inevitably pit communities against each other. Our movement can never question if Keystone XL is worse than Flanagan South (an Enbridge pipeline running from Illinois to Oklahoma), or whether tar sands, fracking or mountaintop removal coal mining is worse. We must reject all these forms of extreme energy for their effects on the climate and the injustices they bring to the people at every stage of the extraction process. Our work must be broad so as to connect fights across the continent into a movement that truly addresses the root causes of social, economic, and climate injustice. We must call for what we really need — the end to all new fossil fuel infrastructure and extraction. The pipeline placed yesterday in British Columbia, the most recent drag lines added in Wyoming, and the fracking wells built in Pennsylvania need to be the last ones ever built. And we should say that.

This narrative has additionally set up a make-or-break attitude about these pipeline fights that risks that the movement will contract and lose people regardless of the decision on them. The Keystone XL and Northern Gateway fights have engaged hundreds of thousands of people, with many embracing direct action and civil disobedience tactics for the first time. This escalation and level of engagement is inspiring. But the absolutist “game over” language chances to lose many of them. If Obama approves the Keystone XL pipeline, what’s to stop many from thinking that this is in fact “game over” for the climate? And if Obama rejects Keystone XL, what’s to stop many from thinking that the climate crisis is therefore solved? We need those using the “game over” rhetoric to lay out the climate crisis’ root causes — because just as one project is not the end of humanity, stopping one project will not stop runaway climate change.

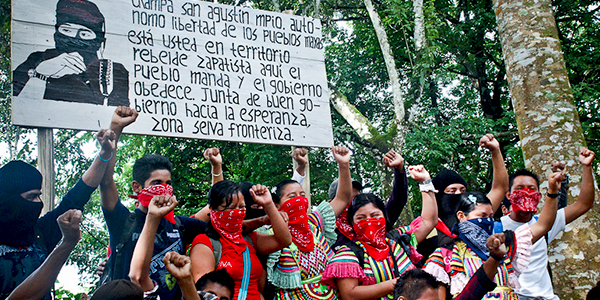

The fights over Keystone XL and Northern Gateway have been undoubtedly inspiring. We are seeing the beginnings of the escalation necessary to end extreme energy extraction, stave off the worst effects of the climate crisis, and make a just transition to equitable societies. Grassroots groups engaging in and training for direct action such as the Tar Sands Blockade, Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance, the Unist’ot’en Camp, and Moccasins on the Ground have shown us how direct action can empower local communities and push establishment green groups to embrace bolder tactics. Our movement is indeed growing, and people are willing to put their bodies on the line; an April poll by the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication found one in eight Americans would engage in civil disobedience around global warming.

However, before the Keystone XL and Northern Gateway mainstream campaigns come to an end, we all must recognize the dangers of having an archway approach to movement building. It is the danger of relying on political power-holders, cutting too narrow campaigns, excluding a systemic analysis of root causes, and, ultimately, failing to create a broad-based movement. We must begin to discuss and develop our steps on how we should shift our strategy, realign priorities, escalate direct action, support local groups and campaigns, and keep as many new activists involved as possible.

We are up against the world’s largest corporations, who are attempting to extract, transport and burn fossil fuels at an unprecedented rate, all as the climate crisis spins out of control. The climate justice movement should have no keystone because we must match them everywhere they are — and they are everywhere. To match them, we need a movement of communities all across the continent and the world taking direct action to stop the extraction industry, finding community-based solutions, and addressing the root causes of the climate crisis.

– – – – – – – – – –

Originally posted by Earth Island Journal and Waging NonViolence.