Editor’s Note: We speak with Kai Huschke, the NW and Hawai’i Organizer for the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund—working to pass Community Bills of Rights that elevate local law and rights above corporate rights. Local initiatives he advised have recently received state-level push-backs. The backlash in Washington State, for example, overturned over 100 years of Washington State legal precedent.

Simon Davis-Cohen: Over a hundred years of Washington State legal precedent has recently been overturned in response to local citizen initiatives you have played an advising role on. Never before had laws in Washington been subject to judicial review before they became law. Using this new tactic, opponents of Bellingham’s, and more recently Spokane’s, Community Bill of Rights have successfully blocked initiatives from appearing on local ballots. Why aren’t you surprised?

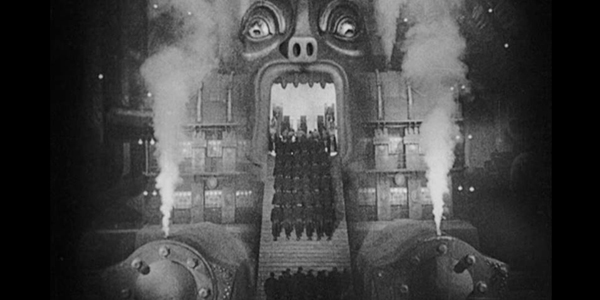

Kai Huschke: It is in these kinds of moments you see the system for what it is in full force, that it has been designed to protect commerce and property interests over rights. In the Bellingham and Spokane cases, the courts said that it is more important to defend corporate interests’ speculative claims of damages rather than uphold the right of the people to vote.

That sounds shocking, and it should be to folks, but why it’s not surprising is that the structure has been built to respond to peoples’ attempts to gain more say over what happens in their community. In Bellingham it was BNSF railroad saying you can’t say no to coal trains because it goes against the Commerce Clause of the US Constitution. In Spokane it was the local Chamber of Commerce, Homebuilders Association, and developers arguing to the judge that you can’t expand rights to residents to decide what happens development-wise in their neighborhoods, institute greater protections for the Spokane River, or expand basic rights for workers, because the local government doesn’t have that authority.

It’s not surprising because the people supporting the Community Bill of Rights in Spokane have always understood that the right to self-government is a complete fantasy. That without taking down the structure we have today – programmed to ignore the rights of people and nature – we should expect more of these kinds of decisions that smash direct democracy.

SDC: In Oregon a similar backlash is taking place—against local efforts to ban genetically modified crops. Oregon’s Governor and State Legislature have taken steps (Senate Bill 863) to remove from localities all governing power over genetically modified crops. How does this illuminate the power structure that already exists in Oregon and other states?

KH: The Oregon Legislature just recently completed the dirty work on behalf of some of the largest corporate agricultural companies in the world by adopting a new law that chokes off any local control over seed for farming. This action shines a big fat light on the fact that a functioning, healthy right to self-government in Oregon communities does not exist. It is the same game that has played out in many other ways in Oregon’s ongoing history and is the way that things play out all over the country.

The corporate interests use the structure of government to drive in preemptive law that functions to crush any semblance of democracy at the community level. The system is very clear that it is about protecting—no matter the costs to people, communities, and the environment—decision making staying in the hands of a few over the best interest of the majority. The few are mainly large corporations that have been expanding this system of preemption as well as guarding against attacks from the people for the last 150 years.

SDC: Both tactics to prevent local bills of rights from being passed argue that certain issues are not within localities’ jurisdiction to govern. What are these issues and why do you think they are within local jurisdiction?

KH: There are a number of things at play around the question of authority. The two clearest elements are state preemption and Dillon’s Rule. State preemption says that some body at the state or possibly the local level (as defined by the state) has all power over certain issues. This means when residents want the right to decide how major development will proceed in their neighborhoods they are denied that right because another entity preempts them. The same scenario can be applied when talking about environmental protections or worker rights. The people and even local government are not allowed to exercise their right to expand rights protections against what the state has claimed it has the authority to regulate.

With Dillon’s Rule it is about the local government only being able to address issues that the state says it can. All power of the local government comes from the state. Powers can be given and powers can be taken away. Spokane, Bellingham, or whatever city you live in, your local government is basically a child to the parent that is the state. The child only can do what the parent allows.

Preemption and Dillon’s Rule fly directly in the face of what the Washington State Constitution says in Article 1, Section 1: “All political power is inherent in the people, and governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, and are established to protect and maintain individual rights.”

The question has always been about (once you realize that what we’ve been told or taught about democracy, self-government, and protecting nature is false) what we are willing to do to change the structure in order to actually elevate and protect the rights of people, neighborhoods, workers, and nature over corporate pursuits.

SDC: In what ways are communities in Washington and Oregon alone? In what ways are they a part of something larger?

KH: Pennsylvania, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Washington, and Oregon have launched statewide community rights networks aimed at supporting local efforts to secure the right to self-government. These five states are also looking at making state constitutional change that would further recognize self-governmental power, eliminate corporate rights, and protect nature’s rights. Ohio will launch the next community rights network, with states like Colorado, Hawai’i, Maine, and Iowa considering doing the same.

Individually at the community level and collectively at the state and federal level, it is understood that we have a structural governmental problem that has to be corrected. Without doing so, the local level assaults by corporations and state governments will continue to escalate. The 160 communities who have passed new law that recognize community rights not corporate rights are the blue prints for what local government should look like as well as what state and federal constitutional change could look like.

In addition the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund has drafted both state and constitutional changes for a variety of states so a very real and very needed discussion can happen around shifting our energy away from issue fights within a rigged system and start to seriously build towards the structural change necessary to incorporate all the issues. More information can be found in the “State Law Center” section of the CELDF website. http://celdf.org/community-rights-state-law-center

SDC: Why is the right of local self-governance important for American grassroots movements?

KH: It is the essence of what American grassroots movements have been about. It was practiced all across the country at various times in our history. It was the major driving force behind the Revolutionaries, encapsulated in the Declaration of Independence and later attempted to be put into practice through the Articles of Confederation.

Rightfully so, the idea of self-governance is fronted as to what it means to be American. The community rights efforts of today are the grassroots to institute true self-government. They are built on the foundation of communities being empowered to elevate civil, political, economic, and environmental rights as they see fit.

Local self-government is the bedrock element. Partnered closely to it is the reality that corporate “rights” must be abolished and that nature’s rights must be recognized. This system change only happens if it comes from the bottom up, is built by the people, and the people move unapologetically forward to make this a reality.

The system we have today is not ours. It is not the legitimate system of the people. It is an unjust system. It is time that the people put in place a legitimate system of governance that protects the rights of people, communities, and nature first and foremost. That only happens when we actually start practicing local self-governance.

– – – – – – – – – –

Originally posted by ReadtheDirt.org here.