By Robert Jensen / Truth-Out

The human species must acknowledge that any future that allows us to retain our humanity will jettison capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy – and be based on an ecological worldview, says Jensen.

(These remarks were prepared for a private conference on sustainability, where the participants critiqued corporate farming, “big ag,” and “big pharma” and industrialized medicine. There was agreement about the need for fundamental change in economic/political/social systems, but no consensus on the appropriate analysis of those systems and their interaction.)

The future of the human species – if there is to be a future – must be radically green, red, black and female.

If we take this seriously – a human future, that is, if we really care about whether there will be a human future – each one of us who claims to care has to be willing to be challenged, radically. How we think, feel, and act – it’s all open to critique, and no one gets off easy, because everyone has failed. Individually and collectively, we have failed to create just societies or a sustainable human presence on the planet. That failure may have been inevitable – the human with the big brain may be an evolutionary dead-end – but still it remains our failure. So, let’s deal with it, individually and collectively.

We can start by looking honestly at the data about the health of the ecosphere, in the context of what we know about human economic/political/social systems. My conclusion: There is no way to magically solve the fundamental problems that result from too many people consuming too much and producing too much waste, under conditions of unconscionable inequality in wealth and power.

If today, everywhere on the planet, everyone made a commitment to the research and organizing necessary to ramp down the demands that the human project places on ecosystems, we could possibly create a plan for a sustainable human presence on the planet, with a dramatic reduction in consumption and a gradual reduction of population. But when we reflect on our history as a species and the nature of the systems that govern our lives today, the sensible conclusion is that the steps we need to take won’t be taken, at least not in the time frame available for meaningful change.

This is not defeatist. This is not cowardly. This is not self-indulgent.

This is reality, and sensible planning should be reality-based.

Let’s Not Deny, Avoid, Evade

So, for all the hard-nosed logical folks who regularly complain that so many people in contemporary culture deny, avoid, evade crucial issues; that so many Americans slip past science when that science has bad news; that so many other people won’t face tough truths, I have a suggestion: Let’s demand of ourselves the rigor we demand of others. Let’s not deny, avoid, evade any aspect of reality.

Another way of saying this: The “things-can’t-be-that-bad” card that so much of the general public plays to trump difficult data is a dead-end, but so is the “we-have-to-have-hope” card that is used to avoid the logical conclusions of our own analysis.

Hope is for the lazy. Now is not the time for hope. Let’s put hope aside and get to the real work of our understanding our historical moment so that our actions are grounded in reality.

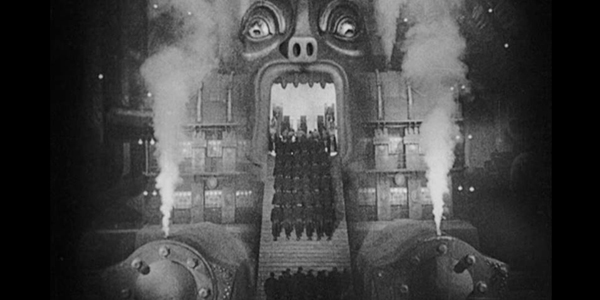

My thesis: Our task today is not to scurry around trying to hold onto the world as we know it, but to focus on how we can hold onto our humanity as we enter a distinctly different era of the human presence on the planet, an era that will challenge our resolve and reserves. Call it collapse or the apocalypse or the Age of Aquarius – whatever the name, it will not look like anything we have known. It is not just the fall of an empire or a localized plague or the demise of a specific ecosystem. The future will be defined by the continuing drawdown of the ecological capital of the planet well beyond replacement levels and rising levels of toxicity, with the resulting social conflict exacerbated by rapid climate destabilization in ways we cannot predict specifically, but that will be destructive to human well-being, perhaps even to human survival.

The thesis, restated: For most of my life, my elders told me that the moral challenge to my generation was how to feed 5 billion, 6 billion, 7 billion, maybe one day, 10 billion people. Today our moral challenge is how to live on a planet of 4 billion, 3 billion, 2 billion, maybe less. How are we going to understand and experience ourselves as human beings – as moral beings, the kind of creatures we’ve always claimed to be – in the midst a long-term human die-off for which there is no precedent? What will it mean to be human when we know that around the world, maybe even down the block, other human beings – creatures exactly the same as us – are dying in large numbers not because of something outside human control, but instead because of things we humans chose to do and keep choosing, keep doing?

If you think this is too extreme, alarmist, hysterical, then tell a different story of the future, one that doesn’t depend on magic, one that doesn’t include some version of, “We will invent solar panels that give us endless clean energy,” or “We will find ways to grow even more food on even less soil with declining natural fertility,” or perhaps, “We will invent a perpetual motion machine.” If I’m wrong, explain to me where I’m wrong.

But, comes the inevitable rejoinder, even if we can’t write that more hopeful story today, can’t we trust that such a story will emerge? Is not necessity the mother of invention? Have not humans faced big problems before and found solutions through reason and creativity, in science and technology? Doesn’t our success in the past suggest we will overcome problems in the present and future?

That response is understandable, but brings to mind the old joke about the fellow who jumps off a 100-story building and, when asked how things are going 90 floors down, says, “Great so far.” Advanced technology based on abundant and cheap supplies of concentrated energy has taken us a long way on a curious ride, but there is no guarantee that advanced technology can solve problems in the future, especially when the most easily accessible sources of that concentrated energy are dwindling and the life-threatening consequences of burning all that fuel are now unavoidable.

Reality-Rejection Stories

Necessity may have been the mother of much invention, but that doesn’t mean mother will always be there to protect us. The technological fundamentalist story of transcendence through endless invention is no more helpful than a religious fundamentalist story of transcendence through divine intervention. The two approaches, while very different on the surface, are popular for the same reason: Both allow us to deny, avoid, evade. They are both reality-rejection stories.

Our chances for a decent future depend in part on our ability to develop more sustainable technology that draws on the best of our science and on our ability to hold onto traditional ideas of shared humanity that are at the core of religious traditions. Technology and religion matter. But their fundamentalist versions are impediments to honest assessment and healthy practice.

If one agrees with all this, there is one more common evasive technique – the assertion, as one media researcher recently put it, that “disaster messages can be a turnoff.” Since most people don’t enjoy pondering these things, it’s tempting to argue that we should avoid presenting the questions in stark form, lest some people be turned off. We should not give in to that temptation.

First, these observations and conclusions are a good-faith attempt to deal with reality. To dismiss these issues because people allegedly don’t like disaster messages is akin to telling people in the path of a tornado to ignore the weather forecast because disaster messages are a turnoff. Just as we can’t predict exactly the path of a tornado, we can’t predict exactly the nature of a complex process of collapse. But we can know something is coming our way, and we can best prepare for it.

Second, let’s avoid the cheap trick of displacing our intellectual and/or moral weakness onto the so-called “masses,” who allegedly can’t or won’t deal with this. When people tell me, “I agree that systemic collapse is inevitable, but the masses can’t handle it,” I assume what they really mean is, “I can’t handle it.” The attempted diversion is cowardly.

When we come to terms with these challenges – when we face up to the fact that the human species now faces problems that likely have no solutions, at least no solutions that allow us to continue living as we have – then we will not be deterred by the resistance of the culture. We will work at accomplishing whatever we can, where we live, in the time available to us. Which brings me to the future: green, red, black and female.

Green: The human future, if there is to be a future, will be green, meaning the ecological worldview will be central in all discussions of all of human affairs. We will start all conversations about all decisions we make in all arenas of life by recognizing that we are one species in complex ecosystems that make up a single ecosphere. We will abide by the laws of physics, chemistry and biology, as we understand them today, realizing the ecosystems on which we depend are far more complex than we can understand. As a result of the ecological worldview, we will practice real humility in our interventions into those ecosystems.

Red: The human future, if there is to be a future, will be red. By that, I mean we must be explicitly anticapitalist. An economic system that magnifies human greed and encourages short-term thinking, while pretending there are no physical limits on human consumption, is a death cult. To endorse capitalism is to sign onto a suicide pact. We need not pretend there exists a fully elaborated plan for a replacement system that we can take off the shelf and implement immediately. But the absence of a fully explicated alternative doesn’t justify an economic system that has dramatically intensified the human assault on the larger living world. Capitalism is not the system through which we will craft a sustainable future.

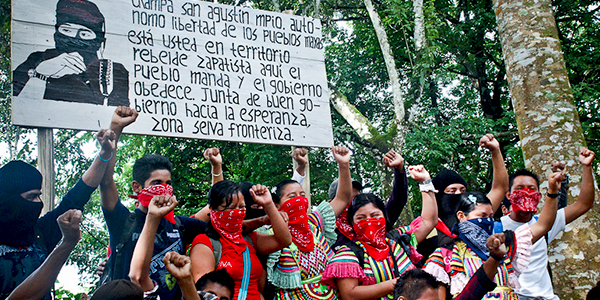

Black: The human future, if there is to be a future, will be black. By that, I mean we have to reject the pathology of white supremacy that has for five centuries shaped the world in which we live, and continues to shape us. Do not confuse this with shallow “multiculturalism” – I am not suggesting that by celebrating “diversity” we will magically create peace and harmony. Instead, we must recognize that the existing distribution of wealth is the product of a profoundly pathological system of racial hierarchy conceived of, and perpetuated by, white Europe and its offshoots (the United States, Australia, South Africa).

Female: The human future, if there is to be a future, will be female. By that, I mean we have to reject the pathology of patriarchy that has for several thousand years shaped the world in which we live and continues to shape us. Again, this should not be confused with the tepid liberal and “third wave” versions of feminism that the dominant culture acknowledges. Instead, we must embrace a radical feminism that rejects the hierarchy and violence on which male dominance depends.

My claim is that we must deal with all these systems in a holistic, integrated fashion, that we will not successfully reject one hierarchal system without rejecting all hierarchical systems. Holding onto any system that depends on one group claiming dominance over another undermines our ability to shape a decent future. We should be dismantling any system based on dominator logic.

Green: Our quest to exploit the larger living world is based on an assumption that humans have a right, rooted in either theological or secular beliefs, to dominate based on our sense of being the superior species. Whether we believe the big brain comes from God or through evolution, in cognitive terms we certainly do rank first among species. But ask yourself, within the human family, is being smart the only thing of value? Do we rank each other only on cognitive ability? We understand that within our species, no one has a right to dominate another simply because of a claim of being smarter. Yet we treat the world as if that status as the smartest species is all that is needed to dominate everything else.

Red: If we put aside the fantasies about capitalism found in economics textbooks and deal with the real world, we recognize that capitalism is a wealth-concentrating system that allows a small number of people to dominate not only economic, but also political decision-making – which makes a mockery of our alleged commitment to moral principles rooted in solidarity and political principles rooted in democracy. In capitalism, domination is self-justifying – if one can amass wealth, one can dominate without question, trumping all other values.

Black: Although the worst legal and social practices that defined and maintained white supremacy for centuries have been eliminated, the white world never settled its accounts with the nonwhite world, preferring to hold onto its disproportionate share of the world’s wealth that was extracted violently. As a result of that moral failing, the material reality and ideological power of white supremacy endures, modified in recent decades to grant some privileges to some of the formerly targeted populations so long as the dominator logic of the system is not challenged. We have not dealt with this because to deal with it, honestly, would mean a dramatic redistribution of wealth, internally within societies and globally, and an even more dramatic shift in the way white people see ourselves.

Female: It is not surprising that the foundational hierarchy of male domination has remained so intractable – to acknowledge the existence of patriarchy is to recognize that patriarchy’s domination/subordination dynamic, which decent people claim to reject, is woven deeply into the fabric of all our lives in every sphere, including sexuality. Taking the feminist critique seriously shakes the foundation of our daily lives. Again, the system’s ability to allow a limited number of women into elite circles, as long as they accept the dominator logic, does little to undermine patriarchy.

This sketch of a radical politics does not mean that every person must always be involved in organizing on all of these issues, which would be impossible. Nor does this short summary of systems of domination/subordination capture every relevant question. But, for those who claim to be concerned with social justice and ecological sustainability, I would press simple points: Everyone’s analysis must take into account all these aspects of our lives; if your analysis does not do that, then your analysis is incomplete; and an incomplete analysis will not be the basis for substantive and meaningful change. Why?

If the story of a human future is not green, there is no future. If the story is not red, it cannot be green. If we can manage to restructure our world along new understandings of ecology and economics, there is a chance we can salvage something. But we will not be able magically to continue business as usual; our longstanding assumption of endlessly expanding bounty must be abandoned as we reconfigure our expectations.

That means we have to start telling a story about living with dramatically less of everything. The green and red story is a story of limits. If we are to hold onto our humanity in an era of contraction, those limits must be accepted by all, with the burdens shared by all. And that story only works if it is black and female. Without a rejection of the dominator logic of ecological exploitation and capitalism, there is no future at all. Without a rejection of the dominator logic of white supremacy and patriarchy, there is no future worth living in.

When someone says, “All that matters now is focusing on ecological sustainability” (asserting the primacy of green), we must make it clear that such sustainability is impossible within capitalism. When someone says, “All that matters now is steady-state economics” (asserting the primacy of red), we must make it clear that such a steady state is morally unacceptable within white supremacy and patriarchy. When someone says, “Talking about sustainability doesn’t mean much for subordinated people suffering today” (asserting the primacy of black and female), we must make it clear that attaining social justice within a rapidly declining system is a death sentence for future generations.

Anytime someone wants to narrow the scope of our inquiry to make it easier to get through the day, we must make it clear that getting through the day isn’t the goal. “One day at a time” may be a useful guide for an individual in recovery from addiction, but it is a dead-end for a species on the brink of dramatic and potentially irreversible changes.

Any time someone wants to think long term but narrow the scope of our inquiry to make it easier to tackle a specific problem, we must make it clear that fixing a specific problem won’t save us. “One broken system at a time” may be a sensible short-term political strategy in a stable world in which there is time for a long trajectory of change, but it is a dead-end in the unstable world in which we live.

To be clear: None of these observations are an argument for paralysis or passivity. I am not arguing that there is nothing to do, nothing worth doing, nothing that can be done to make things better. I am saying there is nothing that can be done to avoid a serious shift, a scale of change that is captured by the term “collapse.” What can be done will be worth doing only if we accept that reality – instead of asking, “How can we save all this?” we should ask, “How can we hold onto our humanity as all of this changes?”

When relieved of the obligation to conjure up magical solutions, life actually gets simpler, and what can be done is easier to apprehend: Learn to live with less. Give up on empty talk about “conscious capitalism.” Cross boundaries of race, ethnicity, class and religion that typically keep people apart. Make sure that both public and private spaces are free from men’s violence. Recognize that central to whatever projects one undertakes should be the building of local networks and institutions that enhance resilience.

We Have Done This

If all this seems like too much to bear, that’s because it is. No matter how flawed anyone of us may be, none of us did anything to deserve this. We shouldn’t have to bear all this. But collectively, we humans have done this. We have done this for a long time, thousands of years, ever since the invention of agriculture took us out of right relationship with the larger living world.

The bad news: The effects of our failures are piling up, and it may be that this time around we can’t slip the trap, as humans have done so many times in the past.

The good news: We aren’t the first humans who looked honestly at reality and stayed true to the work of returning to right relation.

The story we must tell is a prophetic story, and we have a prophetic tradition on which we can draw. Let’s take a lesson from Jeremiah from the Hebrew Bible, who was not afraid to speak of the depth of his sorrow: “My grief is beyond healing, my heart is sick within me” (Jer. 8:18). Nor was he afraid to speak of the severity of the failure that brought on the grief: “The harvest is past, the summer is ended, and we are not saved” (Jer. 8:21)

Along with this prophetic tradition, we also must be willing to draw on the apocalyptic tradition, recognizing that we have strayed too far, that there is no way to return to right relation within the systems in which we live. The prophetic voice warns the people of our failures within these systems, and the apocalyptic tradition can be understood as a call to abandon any hope for those systems. The stories we have told ourselves about how to be human within those systems must be replaced by stories about how to hold onto our humanity as we search for new systems.

We have to reject stories about last-minute miracles, whether of divine or technological origins. There is nothing to be gained by magical thinking. The new stories require imagination, but an imagination bounded by the ecosphere’s physical limits. When we tell stories that lead us to believe that what is unreal can be real, then our stories are delusional, not imaginative. They don’t help us understand ourselves and our situation, but instead offer only the illusory comfort of false hope.

One last bit of good news: If your heart is sick and your grief is beyond healing, be thankful. When we feel that grief, it means we have confronted a truth about our fallen world. We are not saved, and we may not be able to save ourselves, but when we face that which is too much to bear, we affirm our humanity. When we face the painful reality that there is no hope, it is in that moment that we earn the right to hope.

Originally posted by Truth-Out.